When it comes to art and creativity, Indonesia is a real treasure trove. Meet some of these inspiring, creative souls who have left a lasting impression in their respective genres – and will hopefully continue to do so.

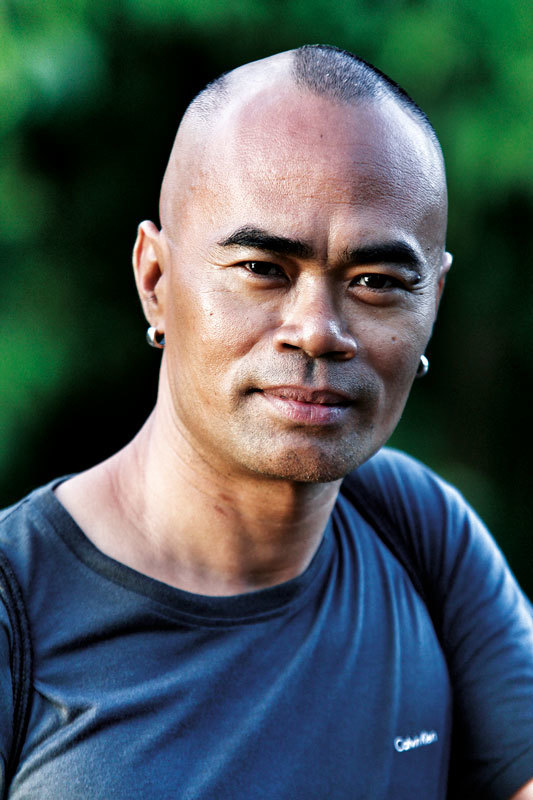

Rizal Iwan

THEATRE

Indonesian actor Rizal Iwan is a rising force in the local performance arts, who continues to draw praises for his acting.

Between April and June 2017, Rizal played a role in a play called “Forgotten Kingdoms” at Rorshach Theatre in Washington, D.C. Written by American playwright Randy Baker, the play portrayed the story of an American missionary in Riau and how his encounter with a young local led to a clash of cultures and faiths between the two men.

Rizal—the only Indonesian in the cast—played the role of Yusuf, the son of a local leader who was involved in spiritual discussions with the American missionary. For Rizal it was the biggest role that he had ever taken on, with the most number of lines that he had ever memorised.

“I was ecstatic, of course. I feel honoured and humbled. Even in my wildest dream I had never imagined that someday I would be performing in the United States, in an American production,” he said.

A film writer and critic himself, Rizal admits that he had been terrified of the possibility that his performance might garner bad reviews from the audience and the press. On the contrary, the play was well received. The Washington Post noted Rizal’s performance as one that “convincingly exudes a reserved wariness”. Meanwhile, DC Metro Theater Arts said the play “is an ocean of meaning within it”.

The solid reviews have served as a mood booster and driver for Rizal, who sees a future in acting.

“I guess I will continue learning by observing the works of other artists, picking their brains and so on. The great thing about the art of acting is that you can learn from basically anything, even by just observing people on the streets,” said Rizal.

Dewi Candraningrum

ART

Dewi Candraningrum is many things: a writer, a feminist, a lecturer, to name only a few. But she is also an accomplished artist.

“I first became interested in art after the birth of my autistic son, I helped him with his painting process, as he cannot converse like a ‘normal’ boy,” she said.

Dewi has spent much of the last years to create the portrait series IANFU. The term refers to young women and girls who were being abducted and forced to sexual slavery by the Imperial Japanese Army during the military occupation between 1931 and 1945, including in Indonesia. Their fate was a cruel one: often, they were not treated as humans, but rather like military supplies.

“I am dedicated to paint their portraits so they won’t be forgotten. They are going to die soon. They never received any justice nor an official apology or compensation from the Japanese government. I hope that these paintings will be a living memory for future generations,” Dewi explained.

For her project, Dewi met quite a few of the surviving IANFU in Indonesia – a challenging task, as she said, yet also satisfying because she was able to give them a voice through art. Dewi also printed the paintings on scarves, which are up for sale.

“When people begin to collect these scarves, the women are no longer treated as ‘the others’ but become special. Moreover, they will receive a part of the funds,” Dewi said. “It may not be a lot, but it comes with a lot of love.”

After showcasing her paintings in an exhibition in Solo, Dewi plans to bring them to Jakarta as well. “They belong to every kindred spirit who aspires gender justice.”

Mouly Surya

FILM

When filmmaker Mouly Surya received an email from the programmer of the Directors’ Fortnight Cannes, informing her that her film “Marlina the Murderer in Four Acts” had been selected for the festival, she almost couldn’t believe it.

“This was a milestone for the Indonesian cinema, mainly because after a 12-year of absence, there finally was an Indonesian feature film selected in the largest and the most important film festival in the world,” she recalled.

Her experience in Cannes was somewhat surreal.

“Cannes is like another world, where movies are what you eat and breathe,” she said. “‘Marlina’ got rave reviews from the critics and a lengthy standing ovation during the screenings, and then you come back home and you were charged overweight fees for your luggage.”

Mouly had been flirting with the idea of making a Western since she first saw images of Sumba Island on Google.

“I wanted to have that classic Asian cinema look along with several Western elements in the film, to make my own impression of a Western,” she said. “I really liked it when a film critic from Variety wrote that the film I made is a new genre, a ‘Satay Western’. We now use the hashtags ‘Satay Western’ or ‘Sate Koboi’ on Cinesurya’s social media channels as well.”

Mouly’s film, which is set in Sumba and will be released in Indonesia by the end of this year, is about feminist heroine Marlina, who struggles to survive and fights for her independence and her integrity.

Mouly is often hailed as one of Indonesia’s most promising filmmakers – but she doesn’t feel any pressure.

“I make films because I love making films, so even if I am bad at it, I will still continue.”

Eko Supriyanto

DANCE

As a featured dancer on Madonna’s “Drowned Tour” in 2001 and dance consultant for Los Angeles and National Tour of Julie Taymor’s “Lion King” Broadway Production, dancer-choreographer Eko Supriyanto needs no introduction.

In the past few years, he had taken a new turn in his career, spending much of his time discovering traditional dance forms and training teenagers in Jailolo, West Halmahera regency in North Maluku. It began with a request from the former West Halmahera Regent Namto Hui Roba to choreograph a colossal dance for the annual Jailolo Bay Festival.

For research purposes, between 2011 and 2012, Eko lived and worked among 350 selected men from the Sahu tribe, none of whom are professional dancers. That period turned out to provide him with immersion into the local culture and a source of inspirations.

Eko went on to create a trilogy. In November 2014, he introduced “Cry Jailolo”, which tells the story of the damage done to the marine ecosystem in Indonesia, especially in West Halmahera. In November 2015, Eko launched “Balabala”, which brings up the story about women in Jailolo.

Both “Cry Jailolo” and “Balabala” have been performed in international festivals and staged in Australia, Japan and France.

His third, called “Salt”, is now in the making and will be launched in Belgium in October and in Indonesia in November. The dance is a reflection of Eko’s life story—from a childhood spent as a farm boy in Central Java, his growth as a dancer to his current life, which included the six years he spent in Jailolo, which by the way also granted him a penchant for the sea and the chance to become a dive master.

Eko’s achievement is not only his own, but one that has also helped preserve and enhance local culture.

Airin Efferin/ Bandung Philharmonic Orchestra

MUSIC

Though the focus is often reduced to one person, the greatest lasting master pieces are usually the result of collaboration. The Bandung Philharmonic Orchestra is poised to become among the best professional orchestras in South East Asia in the next five years, and has made significant strides toward that goal by the end of only its second season, landing Robert Nordling as Music Director and guest soloists such as Leyla Zamora (San Diego Symphony Orchestra) and Bob Stoel (Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra) who not only contribute to their performances but more importantly to the development of their musicians.

The dream started with current Executive Director Airin Efferin, and materialized with the help of colleagues Fauzie Wiriadisastra, Ronny Gunawan, Putu Sandra Kusuma and a host of donors. This diversity and group-effort is a characteristic unique to the Bandung Philharmonic compared to other Indonesian orchestras which tend to center around one or two Patriarchal (or Matriarchal) figures and this may prove key to its perpetual progress and success.

Funding is always a challenge for orchestras which are almost by definition, non-profit. Legislating tax laws which facilitate deductions for donors to the arts can be a true legacy of the country’s current administration.

The Bandung Philharmonic are still somewhat homeless, though they have already proven that fine musicians matter more than a fine concert hall. Yet that is exactly why they deserve one. Therefore, unless the world ends in 2018 and Ridwan Kamil does not get re-elected by a landslide, there will really be no justifiable reason for the Bandung Philharmonic Orchestra not to get a permanent home during his tenure as Mayor. Hopefully it will be as the Wiener Musikverein to Theophil Hansen or Teatro San Carlo to Giovanni Antonio Medrano.

Aan Mansyur

LITERATURE/ POETRY

When he was a kid, Aan Mansyur was obsessed with music and painting, but his mother encouraged him to take up writing.

“Words, she said, are tools to create music, paintings and even dances. She might have said that to calm my desires, for we couldn’t afford to buy musical instruments nor painting equipment,” he said.

He soon discovered that writing was the safest way for him to talk to others, as he thought it was the hardest thing in the world to express his feelings.

“Poems taught me lots of things. When I discover, I write. And by writing, I am discovering,” Aan explained. “Poetry is a world to my knowing, where people come in from so many different places and different beliefs but don’t dispute. In this world of poetry, I meet and dance with hands I couldn’t even hold.”

Aan, who hails from Makassar and has been one of the curatorial members of Makassar International Writers Festival since its inauguration, rose to national fame by writing poems for the movie “Ada Apa Dengan Cinta 2”.

“After I published my poetry book ‘Melihat Api Bekerja’ – an art collaboration project with visual artist Emte – in 2015, I met Mira Lesmana and she asked me to write some poems for AADC2, but I told her that I won’t,” Aan, who is currently working on a poetry book for kids, recalled.

“What I wanted is to write a poetry book for those who don’t love reading poetry, a book that could make the young generation fall in love with poetry, just like I did in junior high school. If we want young people to read poetry, we need to build a bridge for them.”

It worked out perfectly: the success of the film resulted in a renewed interest in Indonesian poetry. When asked where he wants to take his poetry in the future, Aan mused “Perhaps the right question is: where poetry planning to take me in the future? I always need to learn lots and lots of things—and I still see writing poetry as one of the best ways for me to learn.”

Text by Katrin Figge, Sari Widiati and John Paul • Photos Courtesy of DJ Corey PHOTOGRAPHY & DAVID FAJAR