Visiting an exhibition entitled Untouchables, Ciptadana’s annual art exhibition this year, I was reintroduced to the works of Nunung WS. Born in Lawang, East Java, 1948, is a veteran artist who actively appeared in the Jakarta art scene until 2000, when she abruptly moved to Yogyakarta. In the exhibition, her works are juxtaposed against the artworks of Natisa Jones creating quite a stark contrast, which would certainly be interesting to discuss. In many ways it seemed to be too obvious: Nunung is 71, while Natisa is not yet 30. Natisa’s paintings tend to leave traces of figures, while Nunung’s are completely colours and shapes. An art talk on their works was scheduled on Saturday, 23 November 2019 at 2.30 to 4.30pm. A former architecture student of mine, Bunga Yurisdespita, also happened to have an exhibition at Rubanah, and her art talk was on the same day, at 3 to 5pm, so as I was thinking which art talk to go to, I got another idea. As Nunung and Natisa’s works will have been discussed, compared and contrasted in the art talk anyway, perhaps it would be as Bungaing to discuss Nunung’s works in relation to Bunga’s and vice versa. Coincidently, Bunga will also be 30 soon.

“I try to recreate what I had seen, experienced, lived and felt in nature through colour. Painting for me was not bound to form, because existing forms always connect us to something. My aim is to go beyond this, using colour,” stated Nunung WS.

Nunung’s interest in art came from Kartika Affandi inspiration, the artist daughter of Indonesia’s most famous artist, Affandi. Despite family pressure to study religion, Nunung persisted and was admitted to the Academy of Fine Arts in Surabaya (Aksera). Later, under the tutelage of Nashar, Nunung transitioned from the dynamic expressionism of Kartika and her father Affandi to more reflective studies juxtaposing meditative planes of colour. A true propagator of modern Indonesian painting, Nashar once introduced his theory of art as the “Three Nons”: non-technique, non-aesthetic and non-concept. He always told his students to roam free and find their own means of expression. When one of his students asked him about the merit of master painters, he responded, “Don’t you copy his paintings, don’t become a tiny Affandi, a small Sadali or a little Sudjojono. Become yourself!” Indeed, Nashar’s paintings are nothing like any of the other masters. They are colourful compositions of amorphic forms. Sometimes, filled with sweeping curvilinear forms and wild colours, they seem chaotic. Some seem completely abstract. Others hint the presence of animal and human figures. In a few of his paintings, human figures and familiar objects are clearly depicted with the most minimal of means—merely using blocks of colour.

While Nunung was clearly inspired by Nashar, she did not become a “Tiny Nashar”, but she remembers to become herself and became an artist worthy of respect and acclaim. Untouchables curator Emmo Italiander wrote that she is “a masterful and subtle colourist, using luminous hues to create artworks that stimulate and mirror the dreams and emotions of the subconscious. Their beauty and power quickly earned her acclaim, as well as national and international group and solo exhibitions.”

For Nunung, art is about the spirit. “Colour is the most important medium in my work, because it is always there. It dominates every work. I try to step further inside, through the doors of imagination to a world which exists behind the eyes, beyond what is visible, where we can meet something which is more compelling. It is not only beauty but also about the spirit, which I try to express in colours. Colour is my way to total expression.”

Interestingly, although Bunga had of course heard of Nashar and know some of his works, she was not familiar with Nashar’s “Three Nons”. Yet, the young artist’s works also might remind its viewers to the works of Nashar. About Bunga’s work, exhibition curator Gumilar Ganjar wrote: “Intersection between self, space, memory and identity is the essence of Bunga Yuridespita’s work lately. She made her work as a medium to reflect and retrospect by making memory as the starting point. In representing this memory, Bunga then choose to anchor it to specific spaces containing personal memory. For her, the effect of space on a person’s personality is very significant. Such a perspective certainly influenced from her background as an architecture graduate.”

Her paintings emerged from floorplans of different spaces in her life experiences. She reminds us that we comprehend floorplans in many layers. There is the formal layer of the original floorplan as represented in working drawings. But not everyone who experience or use the space are aware of that. They create their own cognitive floorplans as they recognize and comprehend the space. She composes the floorplans in colours and shapes that reflect her cognitive comprehension of the spaces. In so doing, she camouflages the original identity of the spaces, perhaps in a way claiming authorship of them. The final result of her works shows what seems to be purely non-representational forms which actually are representative of many things, her memories of her experiences and her recognition and comprehension of the spaces in which they happen.

Nunung’s approach is actually similar, but her starting point is different. While Bunga starts with her memory or perceptions of spaces, Nunung starting with observing a subject closely until sketches arise in her mind, then she involves her other senses “to provide additional perspectives about the universe and a spiritual state that allows one to sense the universe as a vibration and the centre of all things” observes curator Emmo Italiander. He explains further, “this process requires the artist to develop sensitivity for lines, shapes and colours, and to be able to express what she has in her mind, in her innermost soul, into a new shape, a shape that follows her heart.” Nunung’s approach seems more emotional and spiritual, while Bunga’s artistic approach seems to be more empirical and rational.

The more experienced Nunung also seems freer and more experimental in her choice of medium. Nunung often uses oiled-paper and Chinese painting paper to create horizontal and vertical lines on her paintings. “Most people use oil-paper to wrap foods, but I use it for painting”, she exclaimed. “In human life there’s always a horizontal and vertical line. I represent the horizontal lines as the relationship between humans, and the vertical one as the relationship between humans and their God,” she explains. Indeed, some of her works would remind viewers to the works of Mondrian, who also theorised about the significance of the horizontal and vertical in similar ways.

“Regardless of form and colour, everything is a spiritual experience connected to the abstract form that stems from the self. For me, abstract is a transcendental journey that consists of three, always present, components: magical, mystical and spiritual. For me there is a reality behind the universe. Indeed, understanding abstract art, abstract painting in particular, should not be done with the naked eye. The observer should see it with the heart or with a clear conscience,” Nunung said.

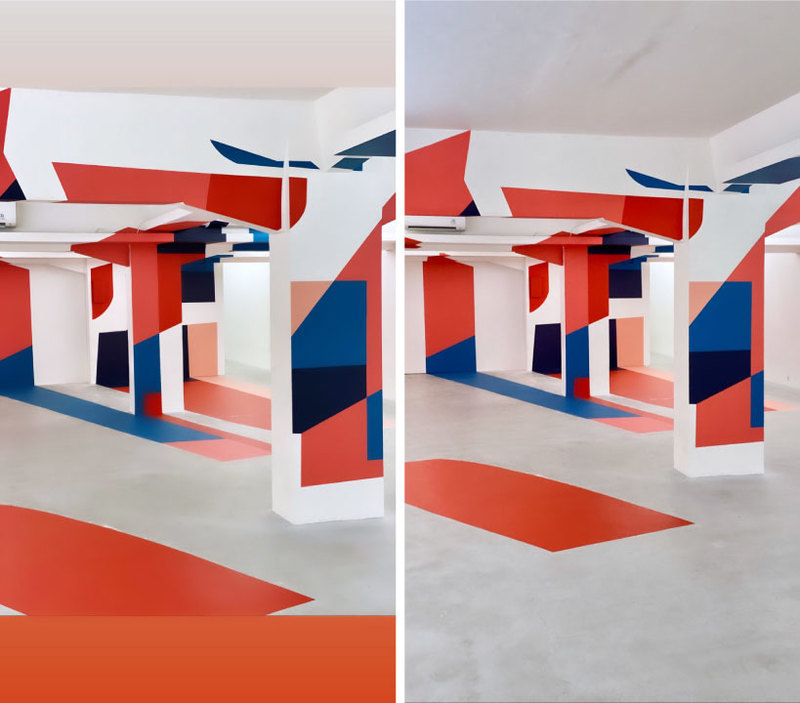

Bunga seems not yet as sophisticated conceptually, but she is young and her experiences as well as her willingness to explore and experiment should make her grow and develop her artistic concepts soon too. Besides a small number of paintings in her solo exhibition, she also prepared an anamorphic installation titled “Brainville, let’s get in.” In this experiment Bunga projected her painting into a three-dimensional ‘plane’, which collides with pillars, walls, ceilings, and also the floor of the space. At a glance it looks like fragments of colour fields chopped and separated from each other. Viewed from a certain vantage point, the separation is then ‘reunited’, forming a typical flat formal configuration commonly found in her paintings. By presenting this rather unusual perceptual experience, Bunga indirectly reminds us that reality depends on perspective. This metaphor would be relevant to the construction of inner values in our culture today: truth is relative and not always certain. Perception alone is no longer able to be a single instrument to ‘see’ reality. It is necessary to adjust one’s perspective in building the meaning of the truth around reality.

Bunga can certainly learn a lot from Nunung, but Nunung may also still learn something from Bunga. “Don’t you copy his paintings, don’t you follow his life experiences, but examine his spirit of life!” reminded Nashar of the merit of master painters. Indeed, learning the spirit of life, does not have to be of master painters, but of anyone who has a great spirit in their approach to life and their work.