Recently there has been a growing interest in the study of art and art history in Indonesia.

The basic knowledge of Indonesian art history has been based on art historical narratives first established by Kusnadi in the early 1950s, continued by Claire Holt later in the decade, and then followed by Sudarmadji and other Indonesian scholars in the 1970s, dividing it into basically 19th century Indonesian art, the “Mooi Indië” period, Persagi and the Revolutionary period, the establishment of the academies, the political turmoil, art in the new order, and contemporary art. Recent developments have been added to the chronological narrative, but other than that nothing much has changed since then although there have been the number of attempts by various scholars to propose alternative approaches.

The Cemeti Art Foundation had actually started to develop an art archive and library of Indonesian art since its inception in 1997. However, in 2007 its founders, which included noted artist Agung Kurniawan, Neni Yustina, Mella Jaarsma and Nindityo Adipurnomo, decided to transform their institution to focus on archiving matters related to Indonesian art, and rename it the Indonesian Visual Art Archives. Although without much doubt it must have been also inspired in part by the formation of the Asian art archives co-founded by Claire Hsu and Johnson Chang in Hong Kong in 2000, this indicated that there was also a growing awareness about the importance of archives in Indonesia.

Some exhibitions started to feature archives, not only as part of the curatorial research, but also as part of the exhibitions. This can be seen in Forum Lenteng’s Videobase (2005), as well as Seni Pesanan (“Commissioned Art”) (2009) and Seni Lukis Tidak Ada (“Art is Non-existant”) (2010), which were curated by Hafiz Rancajale, and Fixer (2011) which was curated by Ade Darmawan, involving the RuangRupa and Forum Lenteng artist collaboratives.

Later on, with the various problems about authenticity in Indonesian art, which reached its peak in 2012, the issue of provenance became more and more important. Hence much more attention was placed on archives than ever before.

Of late, a few Indonesian scholars have separately started to research on exhibitions. In 2016-17, the Postwar exhibition curated by Okwui Enwezor (who recently passed away), was held at Haus der Kunst, Munich. As part of the show it attempted to compile a list of key exhibitions around the world. It was then when I realised that the major even the major exhibitions and Indonesia had not been properly documented. Last year, following a visit to the Netherlands, a colleague from a Dutch museum pointed out the availability of numerous catalogues of art exhibitions held in Indonesia in the 1950s. These catalogs usually listed all the artworks that were shown in the exhibition and sometimes even the prices are included.

Many libraries have also become accessible online. This enabled scholars to remotely search for entries that included names of Indonesian artists and therefore often news and reviews about exhibitions that included the works of these artists could be found and documented.

Scholars from around the world have started sharing materials in their possession with a colleagues on the other side of the world, making research and the possibility of a creation of a global database of art exhibitions much easier than ever before.

This exhibition-based approach is particularly useful in providing information about provenance. With regards to the research on early Indonesian collection, such as the Sukarno collection, in which little or no records exist, information about exhibitions have become particularly useful. Based on the lists of the artworks either coming from exhibition catalogues or news articles, scholars are able to figure out the origins the number of the pieces in the collection, especially when they were purchased from exhibitions. In these cases often the original titles of artworks can be discovered or verified.

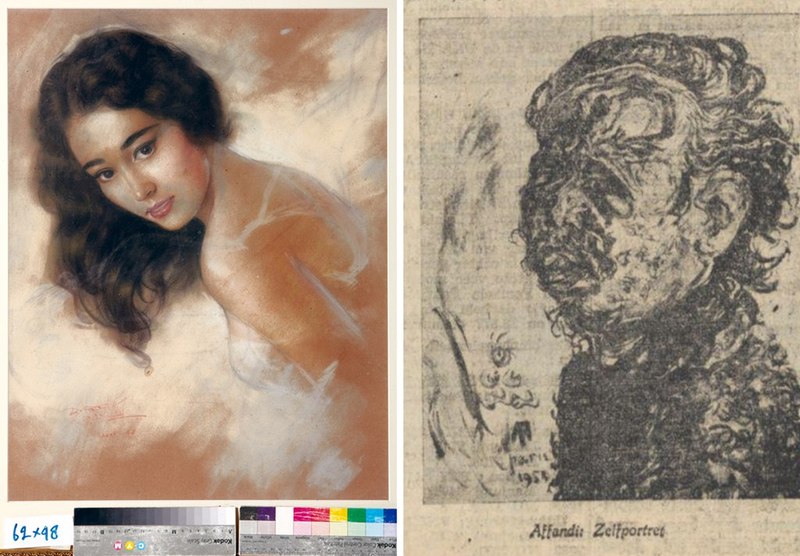

From a news article available through Singapore’s National Library, it is known that Basoeki Abdullah’s portrait of the 1959 “Miss Singapore” Marion Willis was presented to President Sukarno during his visit to the artist’s Tokyo exhibition. The research into the news articles enable us to find out the identity of the sitter.

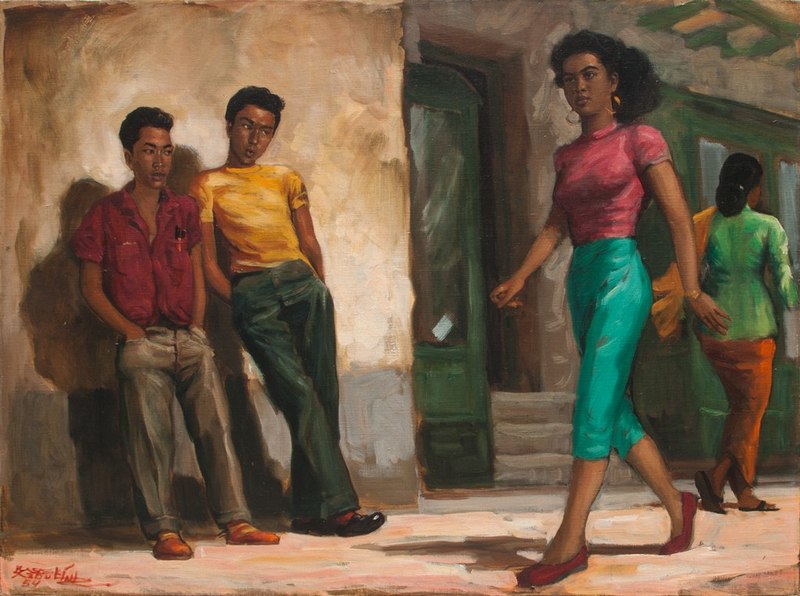

In the Dutch collection exists a catalog of Basoeki Abdullah’s exhibition held at the Hotel des Indes from 12-19 November 1954. During a search into another subject, I found a story that was published in a book by a certain Wenny Achdiat, who mentioned the story of the day she was called into the principal’s office at her school Santa Ursula in the 1950s. The whole time she was walking over towards the office she was worried and wondered she could have done wrong. When she reached office she was surprised to see Basoeki Abdullah, the painter who was her father’s friend, there. Apparently he had been strolling around the Pasar Baru shopping district, and became inspired to work on a painting and wanted her, whom he knew went to school nearby, to be portrayed as the main subject in the painting. She described at the final image of the painting depicted her and some young men in the vicinity of the Pasar Baru shopping district. This description immediately brought to mind the image of a painting I remember the infamous (and considered by some even notorious) Dr. Oei Hong Djien purchased many years ago in an auction in Singapore. Dr. Oei confirmed that the painting dates from 1954 and indeed, the 1954 exhibition catalogs a painting entitled Aduh, Pasar Baru (“Alas, Pasar Baru”). The painting’s provenance is established!

The exhibition-based narrative approach enabled by the availability of online archives will strengthen the chronology-based narrative approach. It will not only help with the identification of the original title of the pieces and also help date undated artworks. Knowledge about the exhibitions in which paintings were presented will also help us have better knowledge about how and in what context they were intended to be featured and what message, if any, they may have been intended to convey. Hopefully scholars around the globe will continue to work to develop and share each of their archives with each other.