At this year’s London Book Fair, which took place from March 12 to 14, Indonesia stepped into the spotlight. As the fair’s Market Focus, organisers presented the country’s literature and culture on an international stage through a diverse programme that included a number of discussions and readings.

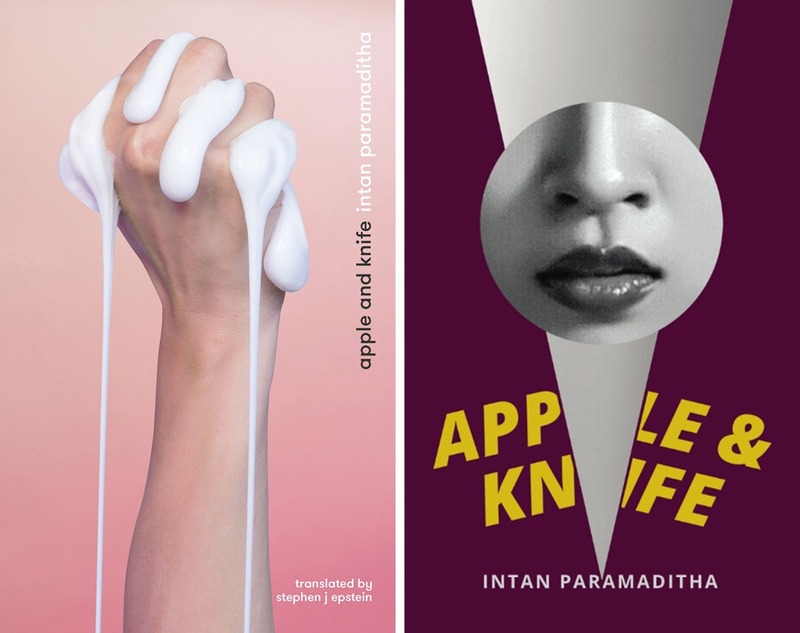

Among the featured authors from Indonesia was Intan Paramaditha, a writer and lecturer in media and film studies at Macquarie University, Sydney. Intan’s debut novel Gentayangan: Pilih Sendiri Petualangan Sepatu Merahmu (“The Wandering: Choose Your Own Red-Shoes Adventure”, 2017) won several awards, while her short story collection “Apple and Knife”, translated by Stephen J. Epstein, was published by Brow Books (Australia) and Harvill Secker (UK) in 2018.

“Apple and Knife” is a collection of feminist horror stories, including rewritings of well-known fairy tales and Indonesian myths. What made you interested in this rather dark subject in the first place?

I have been a big fan of literature and cinema that incorporate elements of horror since I was a teenager. I love reading Mary Shelley, Edgar Allan Poe, Anne Sexton, Margaret Atwood, Abdullah Harahap, Toeti Heraty, and Budi Darma, and my favourite filmmakers are Alfred Hitchcock and David Lynch.

Generally speaking, I see life from a rather dark point of view. I grew up as an angry feminist knowing what women around me, including my mother, had to go through in the patriarchal society. I saw a lot of monstrous acts committed by women, and therefore I became interested in writing about female monsters and ask what kinds of structures create such monstrosity? The older I got and the more I travelled, issues of power relation and inequalities regarding gender, class, race, and religion, did not go away. Instead, they became closer to my daily life and more tangible. It is important to disrupt problematic narratives in our society, and I view horror as a mode that allows us to disturb and interrogate.

You write, among others, about gender and sexuality – something that has not always been very common in Indonesia. Did you have to face criticism for your work?

Actually, I think it has become quite common to talk about gender and sexuality, especially since the early 2000s. Women writers who emerged years before I published my stories, such as Ayu Utami and Djenar Maesa Ayu, have dealt with these issues by writing about sex and sexuality in an explicit manner. When I first published my book in 2005, people put me into the box of ‘women writers who do not write about sex,’ which was quite interesting because I do engage with the discourse of sexuality, though I focus more on its grotesque dimension.

I don’t think I have faced much criticism on my writing, but as someone who consciously claims a feminist position and thinks that writing should be political, I am troubled by the dominant way of viewing literature in Indonesia. There is much emphasis on the formalistic approach in literature, and this perspective valourises the separation between literature and politics with the assumption that arts with a political agenda have less aesthetic value than those that experiment for the sake of literary experimentation itself. For me, all arts are ideological, whether conscious or not, and it is important to have a clear political position.

How would you rate women writers in Indonesia, especially when compared to their male counterparts? Do you think that women face more obstacles when it comes to expressing themselves in writing?

Some women writers enjoy a certain privilege in the literary world. They have won awards and their works have received attention from critics, literary communities and the media. I must say that I myself have been quite privileged on many occasions, but this situation does not apply to the majority of women writers. There are assumptions that works by women writers are always autobiographical. Because they are considered ‘personal’ and not experimental, women writers have not been taken seriously. This has been going on for decades. Since the 1970s and 80s, women have been thought of being too preoccupied with trivial matters, such as romance and domestic relationships, and therefore have been excluded from the larger discourses of politics and nationhood. Such simplistic views of women’s writings were of course propagated by male critics. Today, most literary gatekeepers and decision makers are men. Thus, despite the visibility of some privileged women writers, in general we still have problems with the gender biases in the literary scene.

Feminist issues have been very much in the spotlight recently. But you rightly remarked during one of the sessions at the London Book Fair that feminist writers have been around for a long time – does it bother you that it took the public so long to give feminist writers the credit they deserve, or do you think “better late than never”?

Yes, it is troubling. I am also troubled by the close affinity between neoliberalism and progressive social movement, because suddenly everything is branded ‘feminist.’ The same thing happens to ‘queer.’ The commodification of LGBTQ identity is unlikely in Indonesia, but it does happen in other parts of the world. Nevertheless, I think denouncing your political affiliation because it has been commodified would not solve anything. It’s still important to voice one’s political stance, but this needs to be done with caution, with an awareness that political identity is a sphere of contestation. And since it’s a contestation, why don’t we strategize and use the momentum to draw attention to what have been ignored? This is really the time to reclaim the platform to promote women writers from non-Western societies, who have been voicing their feminist concerns for so long.

How was your overall experience in London? How did you like it, what were the most memorable moments for you?

My book “Apple and Knife” was published recently by Harvill Secker/ Penguin Random House in the UK so it was fantastic to participate in the LBF programme with full support from my publisher, editor, and agent, and to finally meet the people who have read the book. I also had a productive time discussing the publication plans of my novel next year with my UK and US publishers.

One of the most memorable moments was my panel with Norman Erikson Pasaribu and Harry Josephine Giles at Free Word Centre, organised by the English PEN. It was an inspiring transnational exchange of dialogue about what we can do – not just as artists but also citizens on the ground, with our communities – to intervene in public discourse.

Did the Market Focus programme help to shine a light on Indonesian authors? I don’t know. I guess to some extent it did for authors who have established their network prior to the book fair. However, I have questions on how much capital and labour was involved in creating the spectacle of ‘creative industry,’ and I wonder if this was what the audience really needed. In the future, perhaps the government could invest more in funding initiatives that foster strategic and meaningful connections for the books and the authors rather than emphasising spectacularity too much.