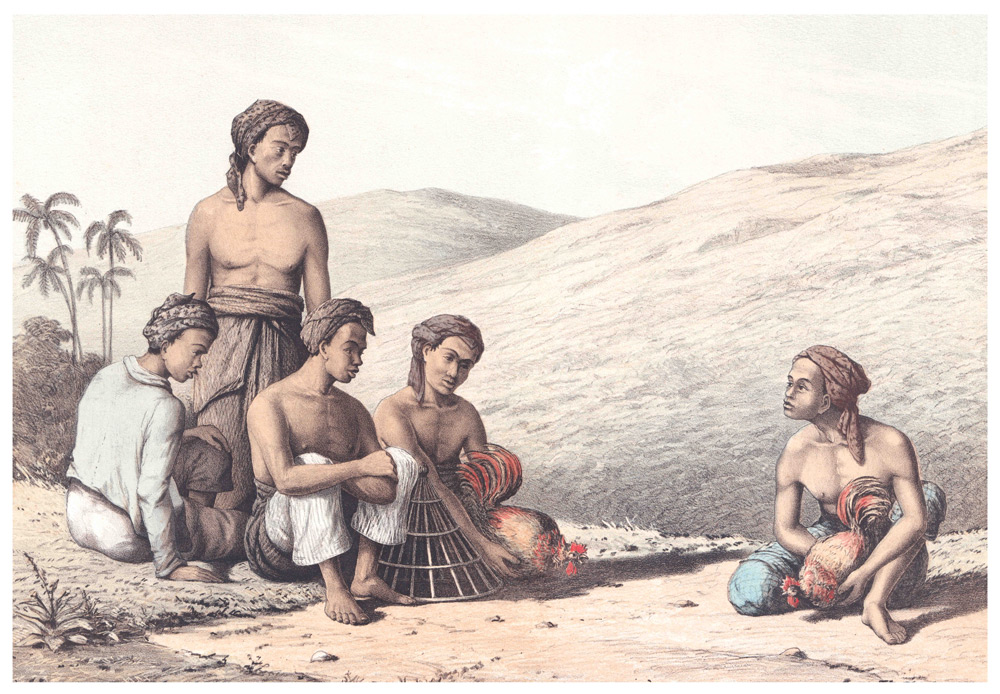

Cockfighting, known locally as tajen or sabung ayam is not merely a pastime in Indonesia; it is a cultural institution deeply intertwined especially with Bali’s spiritual beliefs. Today, it is a familiar image of wicker baskets lining roads around Indonesia, housing roosters as they are toughened up with traffic sounds. In this article, Sake Santema from Indies Gallery presents a few of his antique prints depicting cockfights, a tradition deeply rooted in Indonesian culture.

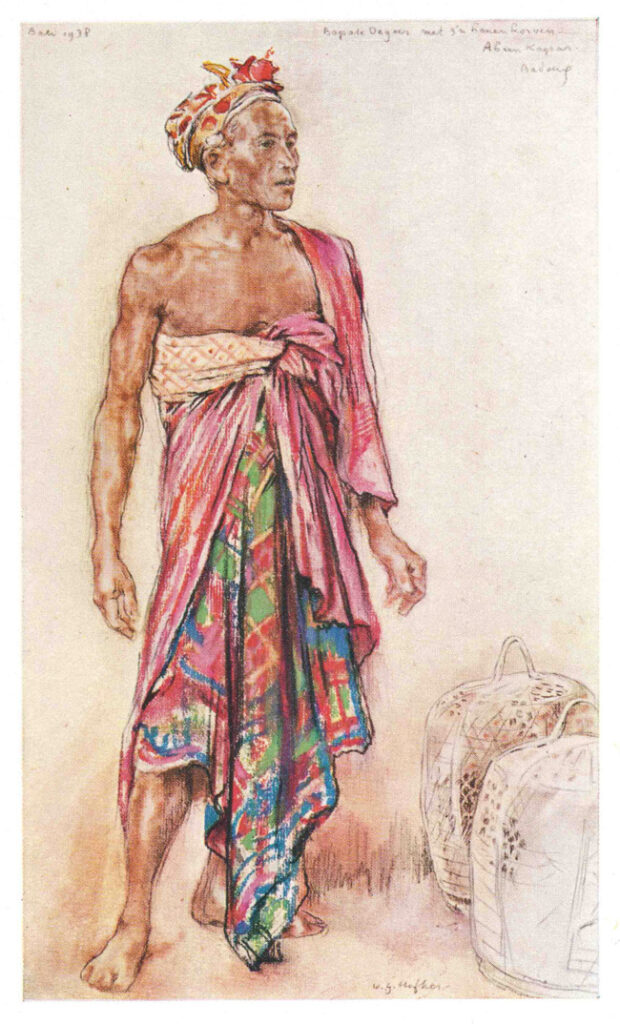

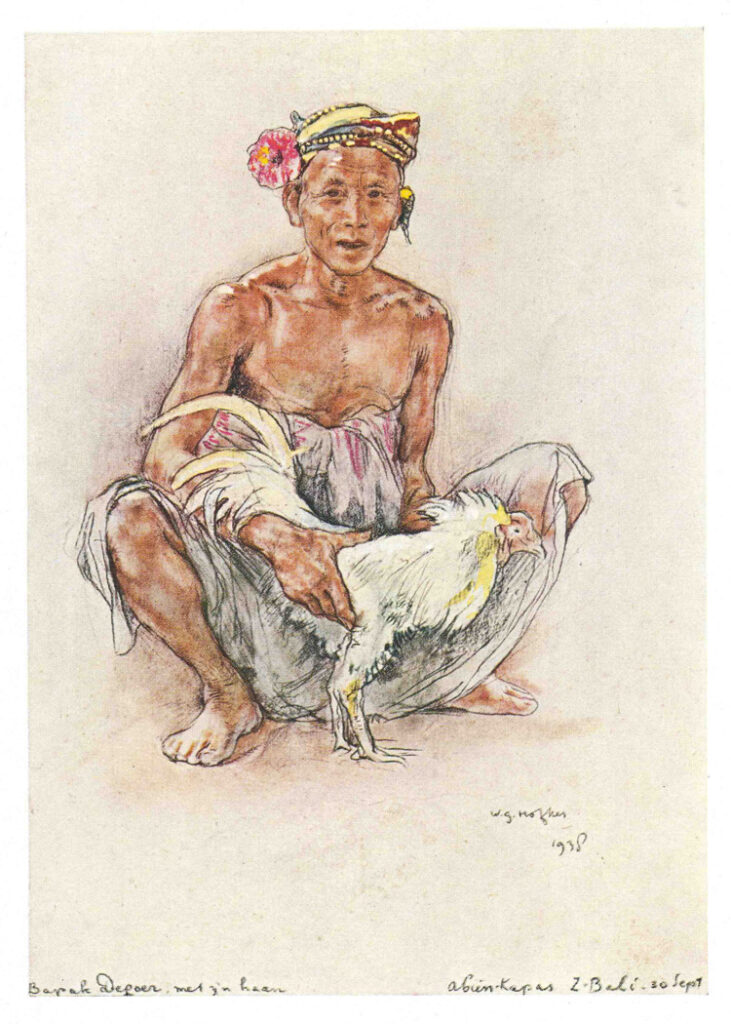

Two 1938 portraits of a Balinese man with his rooster and rooster wickers, by the famous artist Willem G Hofker, who travelled through the archipelago, ending up in Bali. During this trip, he made drawings and paintings of Balinese subjects that were used as advertisements to promote travelling to Indonesia. (Image credit: Indies Gallery Collection)

Ancient Beginnings

The practice of cockfighting in Indonesia can be traced back to the Majapahit era (1293 to 1527), evolving from rituals where animals were considered mediators between humans and the spiritual realm. In Java, Bali, and other regions with strong Hindu-Buddhist influences, cockfights were often associated with temple festivals and ceremonial occasions; a blood sacrifice needed to be made to the local butakala (a class of spirits that are capable of causing harm) to win their cooperation and support.

Every New Year of the Balinese calendar, every community holds a general cleaning-out of bhuta, the mecaru, driving them out of the village with loud and noisy ceremonies. On this day, the Government allows unrestricted gambling and cockfighting, because the land is cured by spilling blood over impure earth. This is followed by a day of absolute stillness and the suspension of all activity. Nyepi, the day of silence, marks the arrival of spring and the end of the troublesome rainy season, when even the earth is said to be sick and feverish.

Cultural Significance

Over time, cockfighting became intertwined with various cultural and religious practices across the Indonesian archipelago. In Balinese culture, tajen are classified into three types, namely Tabuh Rah, Tajen Terang, and Tajen Branangan.

• Tabuh Rah is a Hindu religious ritual where the spilling of blood from a cockfight is necessary as purification to appease evil spirits, and ritual fights follow an ancient and complex ritual as set out in the sacred lontar manuscripts. Many Balinese Hindu believe that roosters that are sacrificed in such ceremonies, as well as the people who sacrifice those animals, will be incarnated into a higher level in the next life.

• Tajen Terang is held to raise funds and develop villages. This type of cockfighting may have elements of gambling but as it receives permission from the authorities and village officials, it is not considered illegal.

• Tajen Branangan is carried out in secret and the location is deliberately made far from the village, so that it cannot be monitored by the authorities. The value of bets can reach millions or hundreds of million rupiah, vs. the value of bets in tajen terang of hundreds of thousand rupiah.

Symbolism in Society

In other parts of Indonesia, cockfighting serves as a popular pastime and social event among communities. Matches were not only opportunities for entertainment and socialising but also occasions for settling disputes or showcasing status through prized roosters. Women and socially disadvantaged people are not allowed to attend cockfights.

Sabung, the word for cock, is used metaphorically to mean a hero or champion. The actual cockfight is a human competition, delegated to animals, where the winner gets respect and admiration from the others, while money is secondary. Indeed, the main players are often the most respected and politically involved members of the community.

The word for cockfight, tajen, comes from tajian, the taji being the blade. The single steel blade and the way it is attached with a red string to the leg of the rooster is an art and has the ability to increase the chances of winning. Lucky tajis are sharpened during a lunar eclipse or only at a dark moon, and should not be seen by women.

Owners and breeders meticulously selected and trained their birds; the best food and care were given to the chosen roosters, receiving massages and living royally for a year or two. Roosters were adorned with symbolic ornaments and received blessings from local spiritual leaders before entering the arena, reinforcing the belief that its performance in the fight was influenced by spiritual forces.

The outcome of each match was often interpreted as a reflection of broader social dynamics; victories brought prestige and honour to their owners and communities, while defeats were seen as signs of displeasure from the spiritual world or indicative of flaws in the preparation of the fight. The losing bird would often be slaughtered as a meal for the winner immediately after the fight.

While its popularity faced occasional suppression during colonial and post-colonial eras, cockfighting remains a deeply rooted tradition in rural areas and smaller communities, where it serves as a means of preserving cultural heritage and fostering social cohesion. However, debates surrounding animal welfare and ethical considerations have prompted efforts to regulate the practice, particularly in urban centres and regions. As Indonesia navigates the complexities of modernity and tradition, cockfighting remains an important cultural heritage.

The works shown in this article are offered for purchase by Indies Gallery, a dealer in authentic maps, prints, books and photographs, dating from the fifteenth to the twentieth century. Indies Gallery also offers these decorative artworks as reprints.

Indies Gallery

www.indiesgallery.com

www.oldeastindies.com